How East Campus Development Policy Shaped Community Relations

~ By Bart Brewer

It’s 7 p.m. on a cold Wednesday evening, and room 202 in the Ford Alumni Center is packed. The coat rack is stuffed and all four rows of chairs are filled as university planners take the podium at a meeting for the Fairmount Neighborhood Association. They are presenting neighbors with plans for updating the development policy of East Campus — plans that will affect the university-neighborhood border along Villard Street.

Villard, with its tree-filled median, has been the University of Oregon’s eastern border for decades. It’s a “graceful edge” that neighbors don’t want to see changed.

Among questions and voices of concern from the crowd, an older man, Danny Klute, stands and raises his hand. People shush each other as he tries to speak.

Klute has spent over 30 years living in Fairmount, being on the association board since the early 2000s. While he has been wary of the university in the past, his view today has softened.

“So 20 years ago, the university agreed to the maintenance of the yards,” said Klute, addressing the university representatives. “I just want to say thank you for following through with that.”

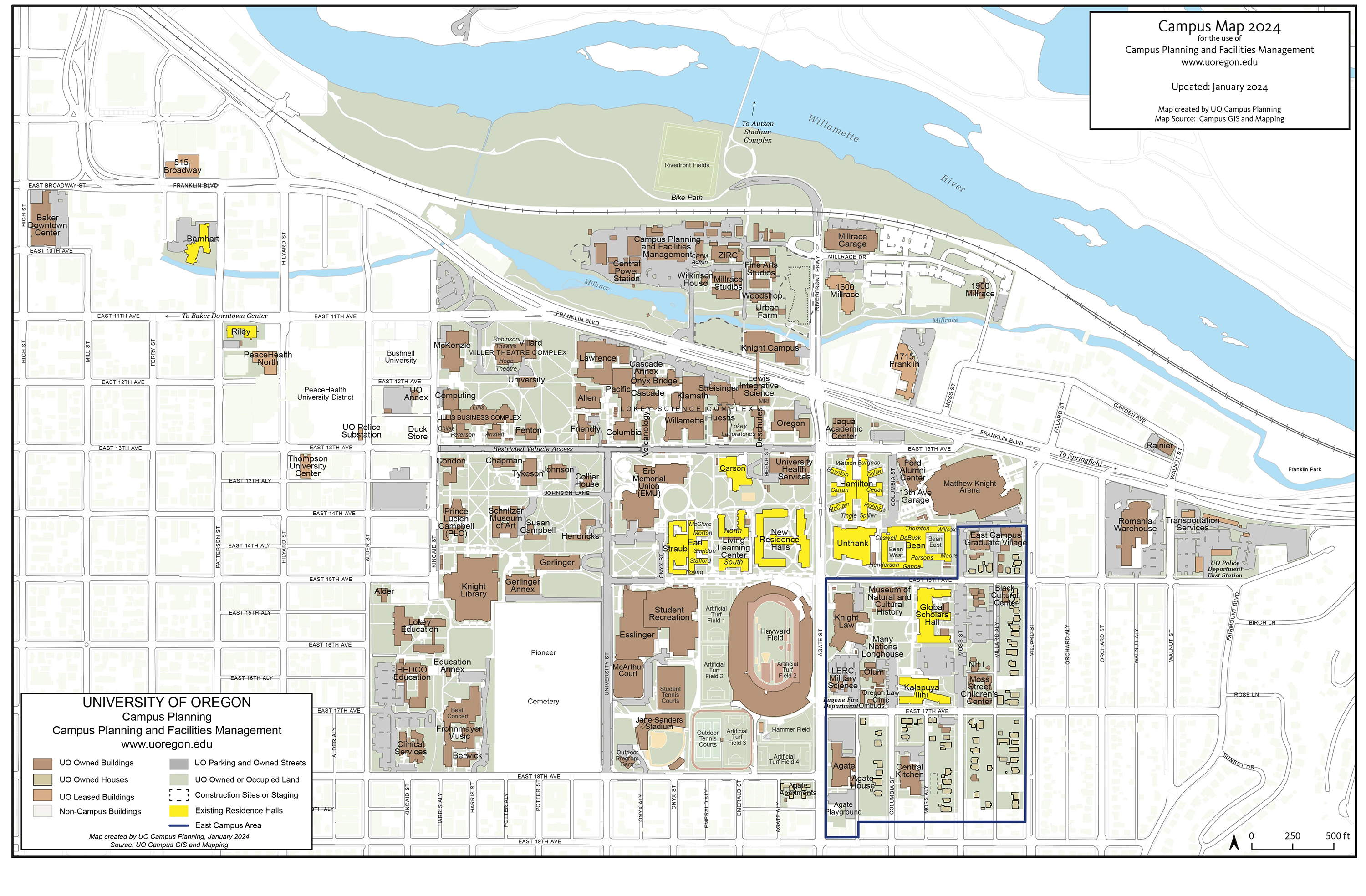

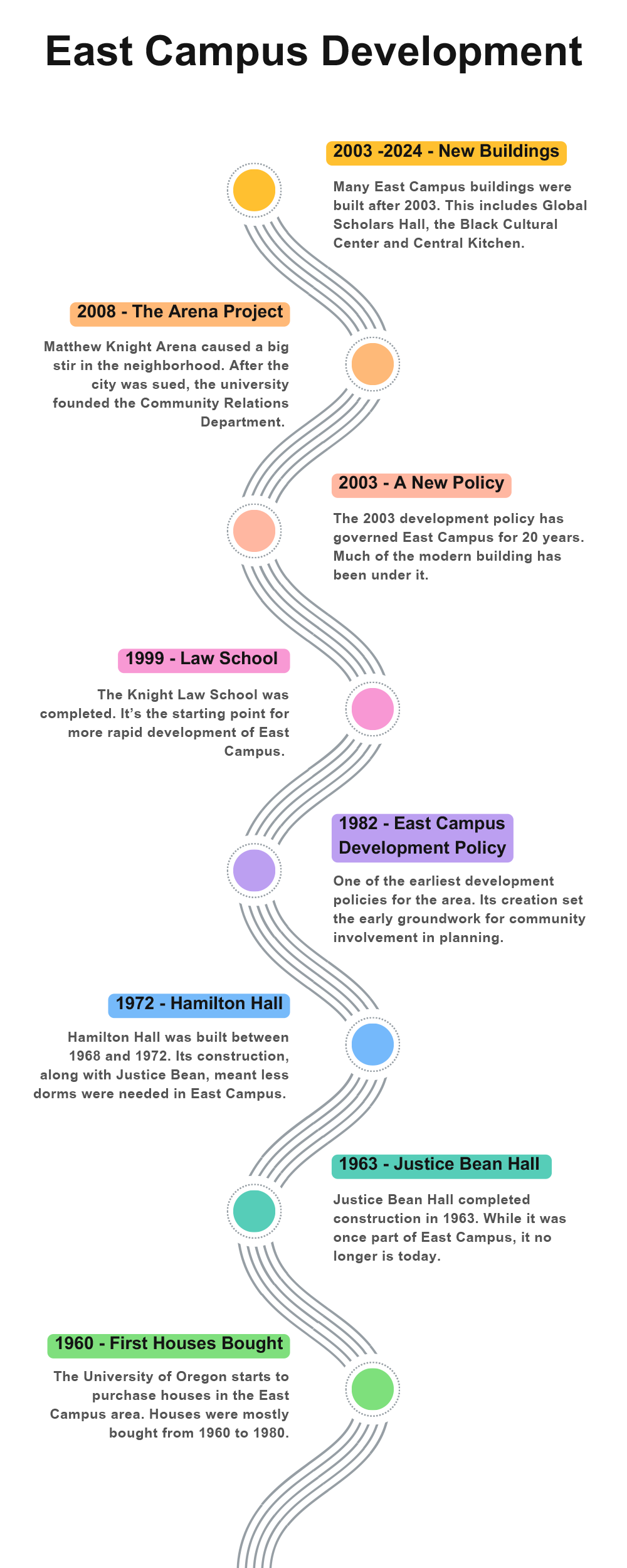

Since the 1960s, the UO has been buying up land in East Campus, a 15-square block area within Fairmount, for future development. Looking south down Villard, the houses don’t show the history of campus expansion clashing with neighborhood pushback. The university, over 60 years, hasn’t always been cordial with neighbors.

The UO gave off a message to the neighborhood that they’re the UO, we can go pound sand.

The 1980s saw poor housing maintenance and slow development that drew ire from the city and residents alike. In 2008, neighbors had to sue in order to get a voice in the construction of Matthew Knight Arena. Only five years later in 2013, the university’s new central kitchen on Moss St. had vents loud enough for residents to hear.

“The UO gave off a message to the neighborhood,” said Susie Smith, another longtime resident of the neighborhood, referring to the construction of the arena, “that they’re the UO, we can go pound sand.”

Now, in 2024, relations between the community and the school will be tested again as the UO looks to update the 20-year-old policy governing the area to make way for Next Generation Housing — new, high-quality dorms built predominantly in East Campus.

“Right now, we’re just at the very beginning of enhancing the vision that started 20 years ago,” said Micheal Harwood, the Associate Vice President of Campus Planning, “and trying to figure out how to continue to develop in a sensitive way to the neighborhood, but also meet the needs of the university.”

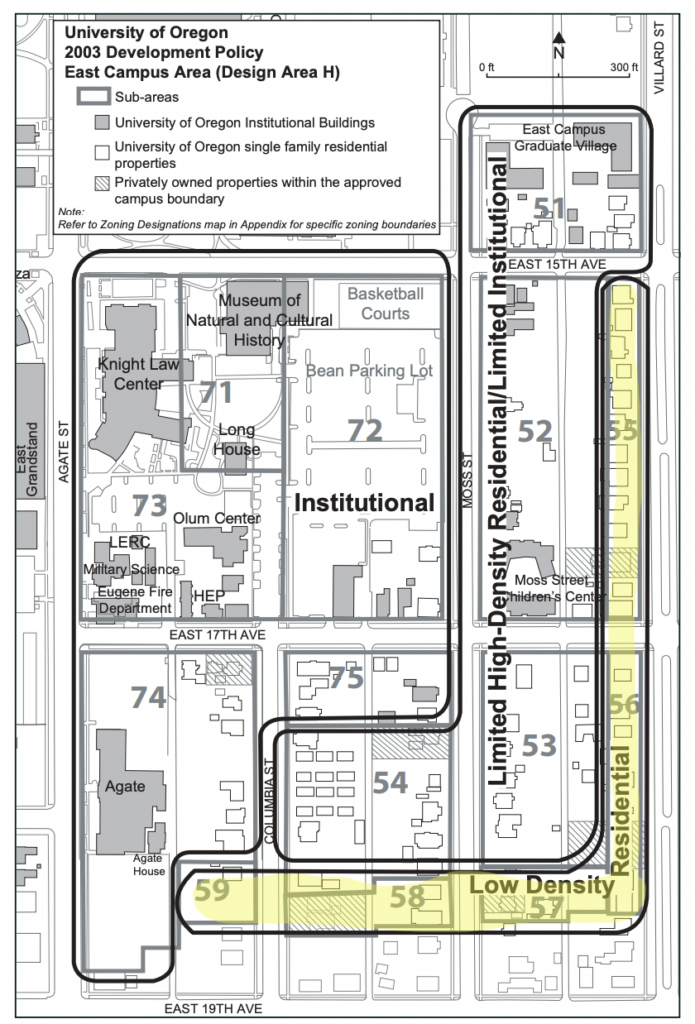

The 2003 Development Policy for East Campus, at time of writing, is the most recent policy addressing the area. It covers everything from development to maintenance, and is where we get the term “graceful edge.”

It’s a promise the university made to neighbors 21 years ago. That promise, amongst others, was that university houses along Villard would hold true to the character of the area.

While that promise has been met in some aspects, the university has faltered in others. Neighbors have had to fight to keep university expansion at bay. Working with neighbors certainly wasn’t always the plan for East Campus.

The Evolution of East Campus

East Campus used to look very different. Before the William W. Knight Law Center was built, there wasn’t much: an old church used by the university as a warehouse and an enormous parking lot with basketball courts. Other than that, it was an assortment of residential houses rented to students.

“The university was purchasing those for the future expansion and development of the campus,” said Director of Housing Michael Griffel. “In the meantime it was trying to make the very best use of them for family and student housing.”

Most of these homes were bought by the university between 1960 and 1980. According to architectural plans from the time, they wanted to rapidly expand into the area. They planned five new dormitories, multiple parking lots along Villard Street and to remove every street within the boundary. A far cry from the graceful edge of today.

Then in the 1970s, priorities changed. While the university had planned five dorms, it ended up only needing two to meet higher enrollment numbers. The Hamilton and Bean dorm halls were completed in the mid-1960s, leaving no need for further construction.

That left the university as a landowner but a reluctant landlord. While East Campus houses would go on to act as student housing, the university would do little to maintain them or develop the area.

That much can be seen in a special area study conducted by the city of Eugene in 1982. It notes how development “leapfrogging” — development that starts and stops over long periods — had negatively impacted the Fairmount neighborhood by causing uncertainty around development. It also noted “steady erosion” of university-owned houses.

Community members grew irritated with how the university had been managing the land. One resident at the time, lamenting the deterioration of historic housing, said, “It looks like what it is, a primarily non-owner occupied, student neighborhood.”

The university responded with the 1982 East Campus Area Development Policy. It promised no more spotty development and increased communication with the community. It would be 20 years before major development started.

“Over time, needs of the campus are evaluated in how to use those spaces,” said Griffel. “To use that land in cooperation with the community for the university’s growth.”

Many recognizable developments, such as Global Scholars Hall and the Kalapuya Ilihi dorm, were constructed under the 2003 development policy. It was a policy forged with community cooperation, though not without some clashing along the way.

2003 Changes and the Graceful Edge

“We would ask for things and they would talk to their lawyers and craft sentences,” said Klute. “I always felt there was a lot of subterfuge going on and it wasn’t fully honest on their side.”

Klute chose to move to Fairmount since it was quieter than the west side of campus. As a member of the Fairmount Board, Klute became part of the Neighborhood Advisory Group that offered input on the 2003 plan. He helped guide the university toward the formal agreement.

“As long as there is a boundary that the university can’t cross,” said Klute, “it has to be a graceful edge.”

The 2003 policy set out to keep the “single-family character” of the area. This came out of fears that the university would continue to expand with large buildings right up to Villard.

“It all got better when we actually sat and talked,” said Klute. “We found that our needs weren’t that far apart.”

The policy was crafted before the university had a community relations department. Neighborhood involvement came down to city codes established by the 1982 agreement requiring it. Despite that, Klute considers it a win.

“We became people,” said Klute.

That doesn’t mean that everything was square between neighbors and the university. According to Klute, who champions personal property rights, the community needs to stay on watch.

“If you look down the street, the university owns that land and they’re growing. And if you ignore that, you ignore that at your own peril,” said Klute. “You have to keep your eye on them and you have to participate in the process.”

Despite improving relations, things had not improved that much by 2008 when the university began plans for Matthew Knight Arena. Situated on the north end of Villard, the university wanted to build the arena without public input.

“The UO said it’s public land and they can essentially build anything they want,” said Smith. “I got up and I said, ‘You mean you can build a nuclear power plant?’”

Smith, who has lived in the neighborhood since 1988, was one of the key players in getting the neighborhood a voice in the arena project. With a background in land planning, she challenged the city’s stance.

The city of Eugene had decided that the UO wasn’t required to go through a site review process for the $227 million arena. That means that the university wouldn’t have to conduct a traffic study, produce management plans or conduct other reviews that would look at the impact an arena would have.

“There were people in the neighborhood that just wanted to fight and stop it,” said Smith. “We told them just trying to stop this thing, they’re [the university] going to win and you’re going to lose.”

She and other association members were able to convince neighbors to file a lawsuit against the city in order to make the university conduct its due diligence.

“I remember the president of the university coming to our neighborhood association meeting and screaming at us,” said Smith. “Saying that we were not just going to roll over the university. It was not a good way to start communications.”

Neighbors came out on top, gaining a seat at the table. Part of what was created through negotiations was a new parking district and the Arena Monitoring Committee, made up of community members.

The arena provided a moment of clarity for the university. If they were to continue to develop eastward, the relation between them and the community would have to change.

“It [UO] needs a more proactive approach to community relationships,” said Matt Roberts, the head of UO Community Relations.

Since joining the department in 2013, Roberts has worked to find a balance between university needs and neighborhood wants. That means allowing for more community involvement and clear signaling to what the university is doing.

“There’s a really good working relationship with the neighborhoods, much more than there was in the past,” said Roberts. “There’s always going to be mitigation necessary for the impacts we have on the neighborhoods. But at the same time, these neighborhoods weren’t here before the university was here.”

Better relations hasn’t always meant better conditions along the graceful edge. Walking along Villard today, Smith points to a university-owned house, 1778 Villard, across the street. A tall chain-link fence surrounds the building. The paint is peeling off. The porch is littered with wooden scrap.

“That one’s been like that for a while,” said Smith.

Despite the 2003 policy, and the maintenance requirements that come with it, houses like 1778 still exist. It’s something that campus planners hope to address with the 2024 revamp.

Plans Moving Forward

The 2024 update means that 20-year-old policy is getting re-worked. Part of the update is a big emphasis on new student housing. Not single family residential, but dormitories that can lure upperclassmen back onto campus enmasse.

“Best practice is to have your students on campus,” said Roberts. “Research has shown that students graduate quicker there and just have a better experience overall.”

Several studies, including one conducted by UO, has shown that students who live closer to campus have better learning outcomes. UO’s study found that students who lived on campus their first year had 0.13 better GPAs, 5% greater retention rates and 8% quicker graduations.

This puts East Campus in a crucial spot. As the least developed part of campus, it has the most potential for residential expansion.

“I really chafe at the idea of calling this East Campus,” said Harwood. “The vocabulary says it is off to the side. It’s not important. I think it’s very important.”

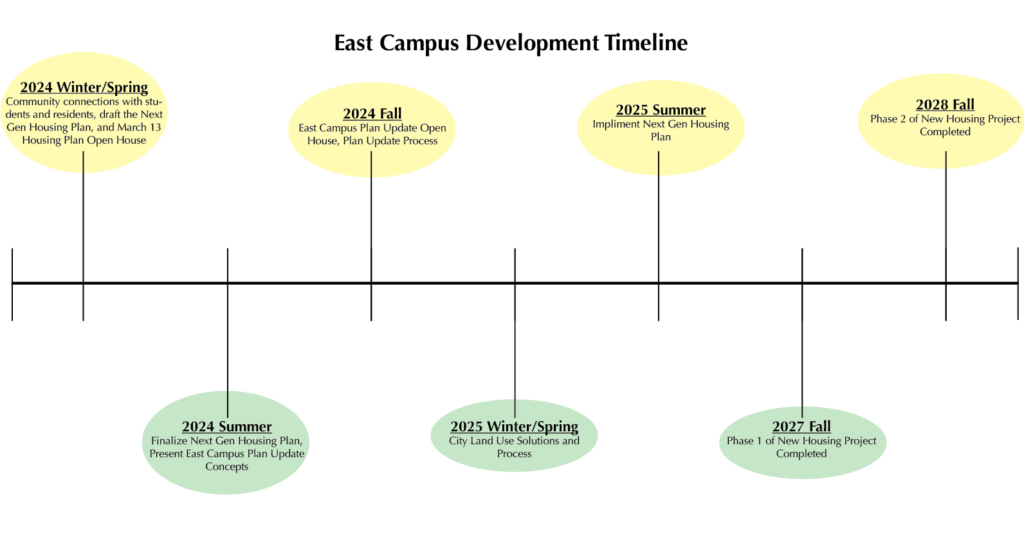

Campus planners have a three-year turn around on what they hope to be Phase 1 of a new East Campus. This year, 2024, is the beginning of that process.

“It’s a 20-year-old document, nothing should stay static forever,” said Harwood. “We’ve started with consultants looking at the big picture.”

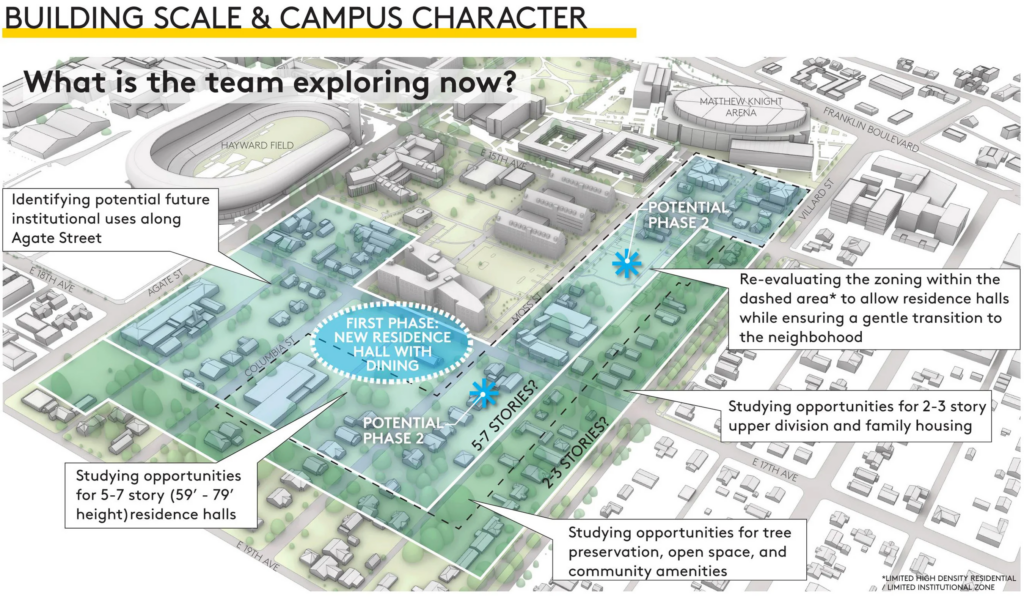

Phase 1 includes plans for a new combined dormitory and dining hall just south of Kalapuya Ilihi, right in the middle of East Campus.

While the cost is still unknown, it will be comparable to Unthank Hall, which cost $80 million to build. Mockups for this phase include raised sidewalks for pedestrians and the possible removal of certain sections of road.

“We’ve been much more engaged and proactive in working with the neighbors,” said Roberts.

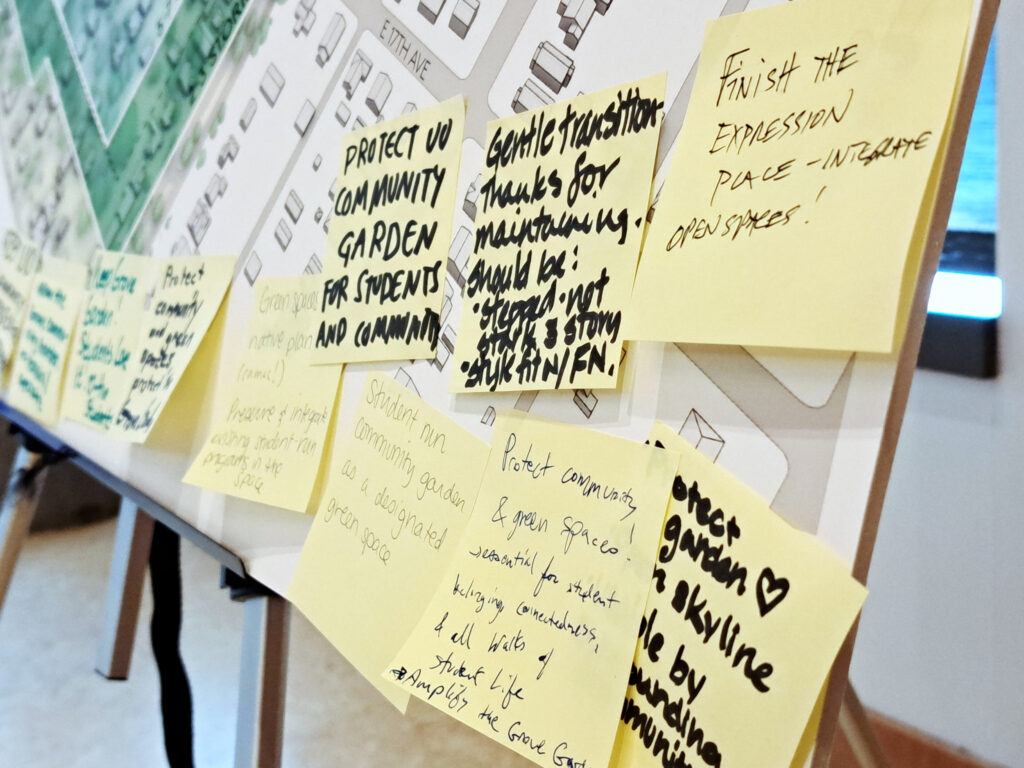

That means more community engagement events, such as an open house the university hosted on March 13. The Lee Barlow Giustina Ballroom was lined with preliminary plans for the area, with campus planners jotting down notes. Residents, UO students and staff all mingled, with conversations breaking out around the mock-ups.

It’s a 20-year-old document, nothing should stay static forever.

One of the biggest concerns came from volunteers and workers of the Grove Garden, located on Moss St., who are worried the new dorm would displace the community garden.

“They don’t make a good faith effort to communicate,” said Valentine Bentz, who has volunteered at the garden for over a year. “The less power we have the more they can cut corners.”

People like Bentz hold up a mirror to those like Klute, who was satisfied with the event. As a smaller group, the Grove Garden is in a similar situation that neighborhood associations used to be in, one without a solid voice.

“There are neighborhood groups in this city that take in hundreds or thousands of acres, and then there’s this little tiny one here and this little teeny tiny one that encompassed the McArthur Court area,” said Klute, “which didn’t give them any power because there’s so few people.”

Time will tell if Community Relations is up to the task of taking on communications outside pre-established neighborhoods and groups that aren’t traditionally represented.

Maintaining the Residential Feel

The 2024 plan will update policy while keeping certain elements from the past intact, namely the graceful edge.

“I told the neighbors just last week, I’ll tell them next week we’re committed to the graceful edge,” said Roberts. “We wouldn’t put a 14-story apartment building along Villard.”

Building height has been a concern for neighbors, especially with zoning laws changing to allow for more stories in residential areas. The university has shown no interest in raising the heights of buildings along Villard.

That doesn’t mean that the same houses will stay along that street forever. Some mock-ups show two-story townhomes on the university side of Villard, something that would alter the graceful edge of today.

Hence a language change planners pushed at the open house to refer to Villard as a “gentle transition.” The university is quick to assure that any development will stay true to the character of the neighborhood.

“We will have building materials and space that fits the neighborhood,” said Roberts at a neighborhood association meeting. “Keep it residential, make it look residential and be compatible with the other side of the street.”

That means keeping a distance from the high-rise style of building that is currently popular along Franklin Boulevard. While the university doesn’t own or develop those buildings, they exist predominantly to house students.

“I’m just going to say I hate, with capital letters, all the stuff that’s being built on Franklin Boulevard, all the new construction,” said Smith. “It looks cheap. It is cheap. That kind of character would wreck the neighborhood quality.”

Most homes that sit along Villard are bungalows styled from the early 20th century. With some exceptions, many were built back in the 1920s to 1940s. One house, 1662 Villard, goes back further, built in 1890.

While high-rises won’t be coming to Villard, it is unclear what direction the university will end up going.

A Policy for the Future

Looking back along Villard, along the graceful edge, houses on the street are going to change.

They could turn into two-to-three story tall graduate housing units. They could become open green spaces. Either way, neighbors will need to keep their voice for the university to maintain community support.

“We’re not going to settle with that, saying that we’ve engaged enough people,” said Roberts, referring to the March 13 open house. “We’re going to have a couple more of those types of events and public meetings.”

Neighbors like Klute are optimistic that community relations will hold solid over the coming years. After living with the graceful edge for 20 years, he hopes it holds true.

“I’m strong for the graceful edge,” said Klute. “I hope we can make a plan that will give us an expectation of how development will work over the next 20 years.”